100% Coverage: Too much and not enough

Code coverage percentage is a controversial subject: some will tell you that you get diminishing returns after 70-80% and it’s not worth bothering, others will say that 100% is not enough. The underlying problem is often the approach taken to testing:

100% coverage as a goal is counterproductive

Code coverage tools tell you how much of your code has been tested, not how well that code has been tested.

- Code coverage only applies to the code you have written, and doesn’t highlight the features you’ve forgotten to implement.

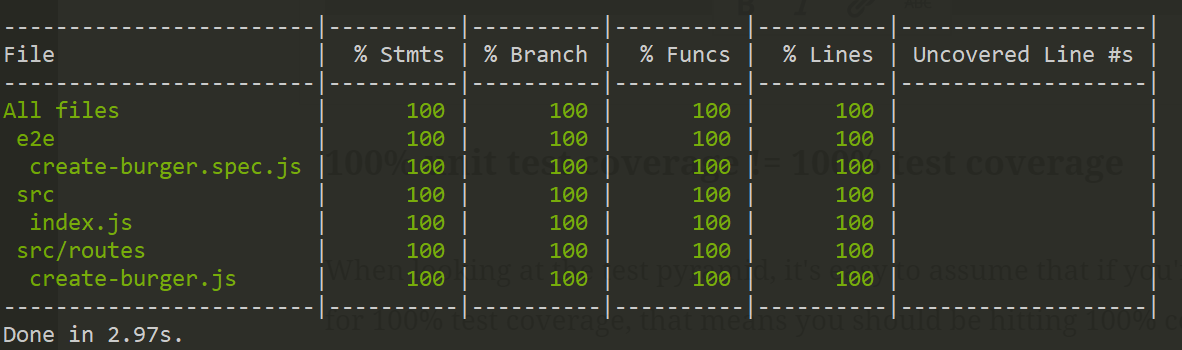

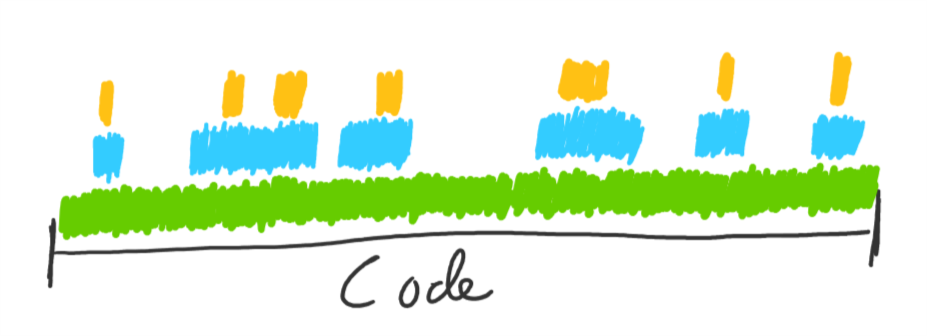

- Achieving high code coverage with low quality is relatively simple, but only results in the code being run, not being tested. It’s possible to hit 100% code coverage with 0 assertions!

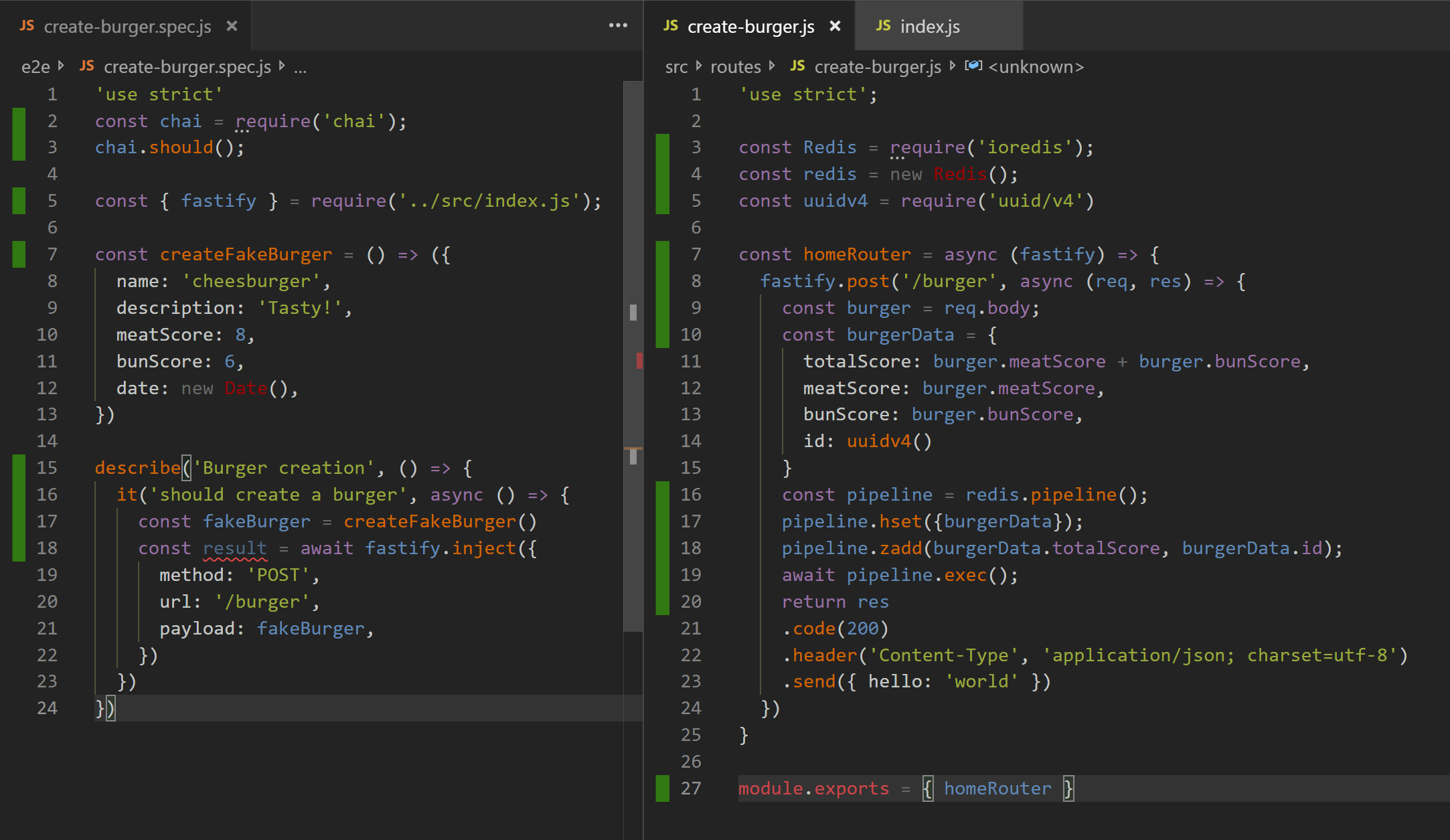

No assertions:

But our tool is happy!

(code on github)

(code on github)

If features drive your testing, you are more likely to find missing code paths and to write assertions for the features. If coverage drives your testing, your are likely to write low quality, brittle tests that satisfy the coverage tool - missing assertions and missing omissions in your logic. This is a problem because:

- Your customer doesn’t care about your coverage, hitting 100% doesn’t help them if your code is still full of bugs. Tests should focus on surfacing bugs, not satisfying tool output.

- You lose insight into the areas that need to be more thoroughly tested: when 100% of your code is covered by low quality tests, your code coverage tool becomes useless.

100% unit test coverage != 100% test coverage

Unit testing glue-code with tonnes of mocks is possible, but the effort-to-value ratio is pretty high: you’ll end up duplicating the same tests at a higher level anyway, and then have more tests to fix when you change that code later.

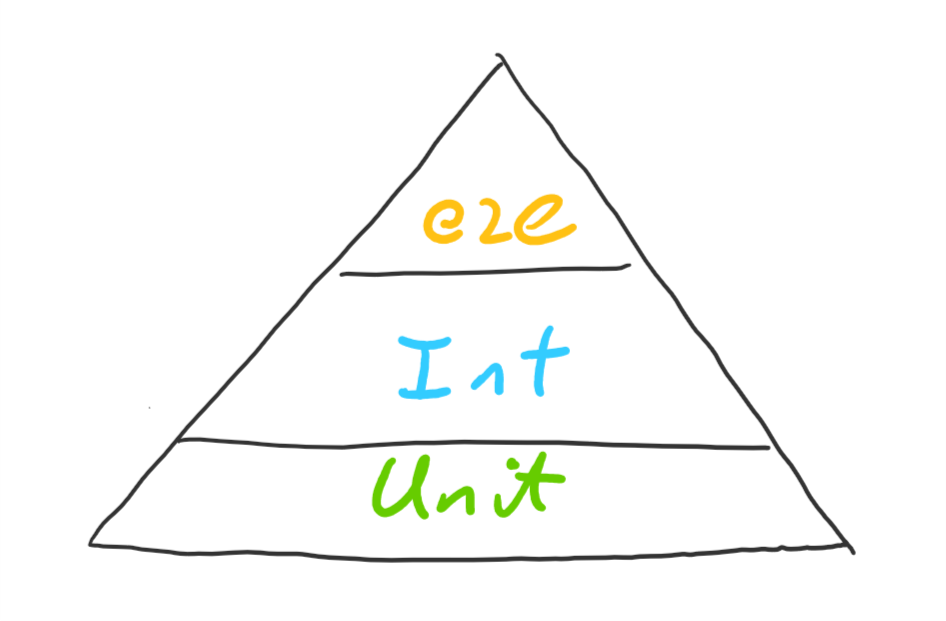

Let’s say we’re testing an API, and we aim for 100% unit test coverage. We’ll use this very professional test pyramid to indicate each testing type:

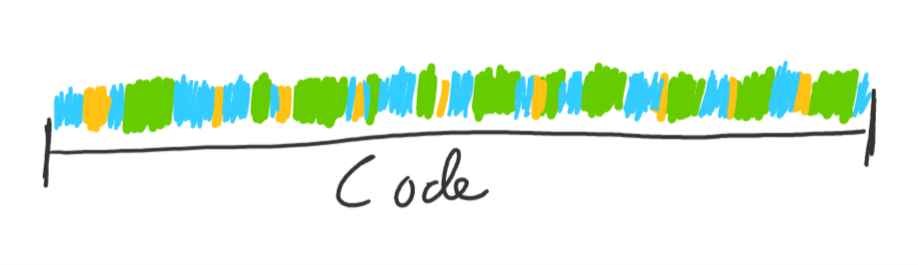

We take our codebase, and test all the business logic using unit tests. Then we notice there’s a bunch of code that isn’t business logic, but does other things like orchestrate other code, access the database, make external calls, etc. So we spend some time stubbing out our code so we can unit test it, and we get to 100% unit test coverage (this is the point where people give up on 100% coverage due to the efort):

Since we also need to test that each unit of code works with each other, we start writing component tests on top of our unit tests, and then some end to end tests that tests a few happy paths:

At this point, since we have 100% unit test coverage, the component and e2e tests overlap the unit tests and we end up directly testing the same chunks of code more than once. The difference is that the component tests (for non business-logic code) are easier to write, do a better job of testing since they test against real code instead of mocks, and are less likely to break when the code changes.

If we reduce the scope of our unit tests down to just code that can easily be tested (the business logic), the other layers of testing can fill in the gaps and help us reach 100% total coverage with better confidence in our tests, less overlap, and less effort (since we wrote fewer tests with fewer stub):

Not all code is equal

Some code is much more important than other code. Your focus should be on testing the important code thoroughly, not in wasting effort setting up mocks for the less important code.

Some projects have more risk than others. Are you writing banking software for millions of paying users, or a side project for fun? Scale your testing time appropriately.

Conclusion

Use your product requirements to drive testing. Use the risk factors of your product to determine how thorough your tests need to be. Use your code coverage tool as a tool, to tell you where best to spend your limited amount of time, not as a goal to give you a false sense of security.

Related reading: